How Surveys Can Help Fundraisers Uncover the 4 Main Drivers of Donor Loyalty

Full Platform Overview Chat With Us

Full Platform Overview Chat With Us

What is it that drives donor loyalty?

What are the determinants of longer term value?

These are questions we’re often asked at Bloomerang and we’ve been working to develop measures that all our clients can use to track how well they are doing at bolstering future donor retention.

We know from research conducted by myself and my colleagues over 25 years that there are four key drivers of loyalty that nonprofits need to be attending to.

The first is how satisfied people are with how they have been treated as donors.

Have they been properly thanked?

Do they get a timely response to any issues or concerns?

Are they asked appropriately and for what they deem appropriate sums?

Clearly we can’t ask questions about every aspect of service quality, but the good news is that we don’t have to. It is only necessary to measure a few components to get a sense of how people feel about the service in general.

So, did we just pluck this idea from the ether?

No.

You’ll know from the commercial world that customer satisfaction surveys are now ubiquitous and they are ubiquitous for a reason. It is now well established that satisfaction has a strong positive effect on loyalty intentions in a wide variety of product and service contexts (Fornell et al 1996; Mittal and Kamakura 2001) including fundraising.

In the first study to address donor satisfaction (Sargeant 2001) we identified a positive correlation with loyalty; donors indicating that they were ‘very satisfied’ with the quality of service provided being twice as likely to offer a second or subsequent gift than those who identified themselves as merely satisfied. More recent work (by Sargeant and Woodliffe, 2006) has confirmed this relationship, while in the latter case simultaneously identifying a link between satisfaction and commitment to the organization. Work by Bennett and Barkensjo (2005) similarly provides support that there is a significant and positive relationship between satisfaction with the quality of relationship marketing activity (in this case, relationship fundraising) and the donor’s future intentions and behavior, particularly the likely duration of the relationship and the levels of donation offered.

Despite the weight of evidence that it is the single biggest driver of loyalty, few nonprofits actually measure and track levels of donor satisfaction over time (Sargeant and Jay 2004, Burk 2003). That said, a number of major charities are now measuring and tracking donor satisfaction, with a handful constructing supporter satisfaction indices that can be fed into their organizational reporting systems (e.g. a balanced scorecard). Managers are thus now being rewarded for changes in the level of aggregate satisfaction expressed.

From where we sit this seems a long overdue practice.

Of course loyalty is a function of much more than just how people feel about their experience with fundraisers. It is also a function of whether they believe they are having an impact on the beneficiaries or cause. The difficulty for most donors though is that they have no objective way of knowing whether the money they gave actually delivered the requisite benefits. Donors can’t typically see the service being delivered. So the mechanism for most of our donors is one of trust. Do they trust that the organizations is doing what it says it is doing and do they trust that it is spending its money wisely.

In the commercial sector successive studies have demonstrated how trust drives customer loyalty when other factors such as commitment are held constant (e.g., Gournaris, 2005; Hart & Johnson, 1999; Ranaweera & Prabhu, 2003a). For example, Ranaweera and Prabhu (2003b) report that customer loyalty and positive word of mouth reviews by customers are positively related to a customer’s trust in the service provider. These authors also determined that highly satisfied customers with low trust levels have significantly lower levels of loyalty intention.

In fundraising, Sargeant and Woodliffe 2007 have demonstrated empirically the impact of trust on giving and this is further supported by data from the About Loyalty project (Sargeant and Lawson 2015).

The relationship marketing literature suggests a further driver of customer loyalty, namely relationship commitment (Bendapudi and Berry 1997, Morgan and Hunt 1994). Moorman et al (1993) define this as a desire to maintain a relationship, while Dwyer et al (1987) regard it as a pledge of continuity between two parties. What these definitions have in common is sense of ‘stickiness’ (Gustafsson et al (2005) “that keeps customers loyal to a brand of company even when satisfaction may be low” (p211). It differs from satisfaction in that satisfaction is an amalgam of past experience, whereas commitment is a forward looking construct.

Sargeant and Woodliffe (2007) found that there are actually two types of commitment. The first is what they term ‘passive commitment.’

In their study a significant number of individuals ‘felt it was the right thing to do’ to continue their support, “but had no real passion for either the nature of the cause or the work of the organization.” (p53). Indeed some supporters, particularly regular givers (sustainers) were found to be continuing their giving only because they had “not gotten around to cancelling” or had actually forgotten they were still giving. By contrast, Sargeant and Woodliffe also identify active commitment which they define as a genuine passion for the future of the organization and the work it is trying to achieve. The literature suggests that this ‘active’ commitment may be developed by enhancing trust (Sargeant and Lee 2004), enhancing the number and quality of two way interactions (Sargeant 2001 and Sargeant and Woodliffe 2007) and by the development of shared values (Swasy 1979, Sargeant and Woodliffe 2007). Other drivers include the concept of risk which the authors define as the extent to which a donor believes that harm will accrue to the beneficiary group were they to withdraw or cancel their gift and trust, in the sense of trusting the organization to have the impacts that it promised it would have on the beneficiary group or cause.

Finally, the authors conclude that the extent to which individuals believe that they have deepened their knowledge of the organization through the communications they receive will also impact positively on commitment. The authors term this latter concept ‘learning’ and argue that it serves to reinforce the importance of planning ‘donor journeys’ rather than simply a series of ‘one-off’ campaigns.

The final driver of loyalty is the notion of intimacy. As relationships become more intimate, the breadth and depth of the bond increases. The more their interdependence grows, the stronger the emotional experience becomes for both partners (Clark and Reis, 1988). A number of studies have now examined the role intimacy plays in marketing relationships. Yim et al. (2008), for example, identify intimacy as an important driver of customer loyalty in consumer relationships, while Hansen et al. (2003) note that consumers are willing to share information with (or about) service providers they normally would not in intimate relationships.

Yim et al. (2008) and Bügel et al. (2011) see intimacy as feelings of closeness, connectedness and bondedness and findings indicate that customer-firm intimacy has positive effects on trust, commitment and loyalty. It seems particularly impactful in what are termed high involvement situations (Yim et al 2008) where individuals reflect in more depth on their decisions and the meaning behind them. It is of course possible to imagine many scenarios where charitable giving is deeply meaningful for the individual and hence we include it here.

Our early testing in fundraising has suggested that intimacy should be measured alongside satisfaction, commitment and trust. Although related it adds significant additional explanatory power to models of loyalty (Bügel et al. (2011). It also drives how good people feel about offering their support and thus contributes substantively to feelings of donor wellbeing. In our current survey we follow Yime et al and operationalize intimacy as a feeling of closeness.

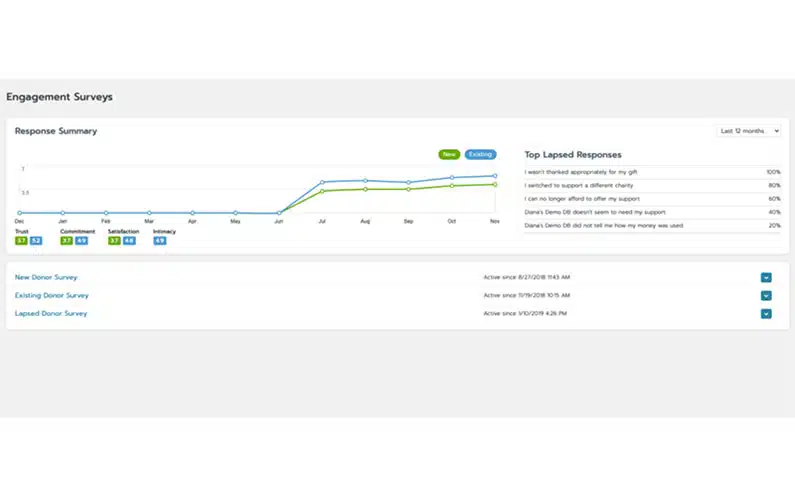

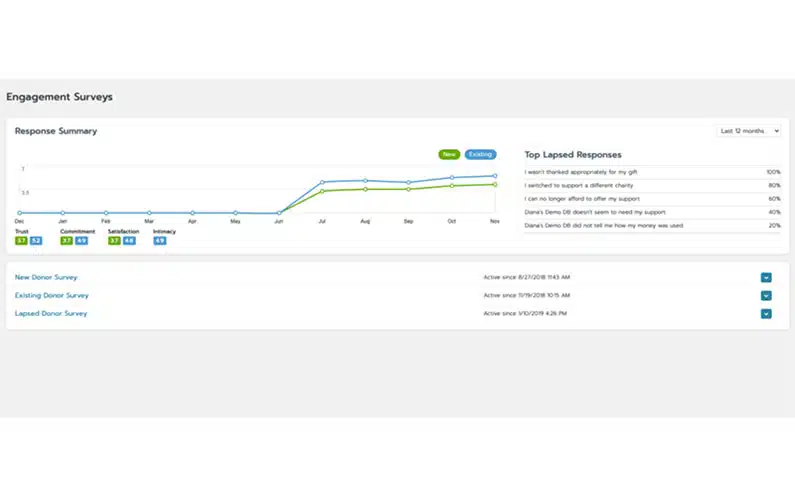

All of these concepts have the power to drive donor loyalty, so our Engagement Surveys in Bloomerang will give you a sense of how you are doing and doing relative to others. It will give you a sense of the elements of a relationship you’re handling well and where there might be scope for improvement. And of course you can now track that improvement over time.

References:

Bendapudi, N. and Berry, L.L. (1997) Customers’ Motivations for Maintaining Relationships with Service Providers. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 15-37.

Bennett, R., and Barkensjo, A. (2005) Causes and Consequences of Donor Perceptions of the Quality of the Relationship Marketing Activities of Charitable Organizations. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 13(2), 122-139.

Bügel, M. S., Verhoef, P. C., and Buunk, A. P. (2011) Customer Intimacy and Ommitment to Relationships with Firms in Five Different Sectors: Preliminary Evidence. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(4), 247-258.

Burk, P. (2003) Donor Centred Fundraising. Cygnus Applied Research Inc / Burk and Associates Ltd, Chicago.

Clark, M.S. and Reis, H.T. (1988) Interpersonal Processes in Close Relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 609-672.

Dwyer F., Schurr, P. and Oh, S. (1987) ‘Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships’. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11-27.

Fornell, C., Johnson, M.D., Anderson, E.W., Cha, J. and Bryant, B.E. (1996) ‘The American Customer Satisfaction Index: Nature, Purpose and Findings’. Journal of Marketing, 60(Oct), 7-18.

Gustafsson, A., Johnson, M.D. and Roos, I. (2005) ‘The Effects of Customer Satisfaction, Relationship Commitment Dimensions and Triggers on Customer Retention’. Journal of Marketing, 69(October), 210-218.

Hart, C.W. and Johnson, M.D. (1999) A Framework for Developing Trust Relationships. Marketing Management, 8(1), pp20-22.

Mittal, V. and Kamakura, W. (2001) ‘Satisfaction, Repurchase Intent, and Repurchase Behavior: Investigating The Moderating Effects of Customer Characteristics’. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(Feb), 131-42.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R. and Zaltman, G. (1993) ‘Factors Affecting Trust in Market Research Relationships’. Journal of Marketing, 57 (1), 81-101.

Morgan, R. and Hunt, S. (1994) ‘The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing’. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20-38.

Ranaweera, C. and Prabhu, J. (2003a) The Influence of Satisfaction, Trust and Switching Barriers on Customer Retention in a Continuous Purchasing Setting. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(4), pp374-395.

Ranaweera, C. and Prabhu, J. (2003b) On the Relative Importance of Customer Satisfaction and Trust as Determinants of Customer Retention and Positive Word of Mouth. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 12(1), pp 82-90.

Sargeant, A. (2001) ‘Relationship Fundraising: How To Keep Donors Loyal’. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 12(2), 177-192.

Sargeant, A. and Jay, E. (2004) Building Donor Loyalty. Jossey Bass, San Francisco.

Sargeant, A. and Lawson, R. (2015) Learning About Loyalty: Lessons from Research. International Fundraising Congress, Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands, October.

Sargeant, A. and Lee, S. (2004) ‘Donor Trust and Relationship Commitment in the U.K. Charity Sector: The Impact on Behavior’. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(2), 185-202.

Sargeant, A. and Woodliffe, L. (2007) ‘Building Donor Loyalty: The Antecedents and Role of Commitment in the Context of Charity Giving’. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 18(2), 47-68.

Swasy, J.L. (1979) ‘Measuring the Bases of Social Power’ In Wilkie, W.L. (Ed) Advances in Consumer Research, 6, Ann Arbor: Association for Consumer Research, 340-346.

Yim, C.K., Tse, D.K., & Chan, K.W. (2008) Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: Roles of customer-firm affection and customer-staff relationships in services. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 741-756.

Comments

Sue Gifford